Moving from emptiness to savouring life

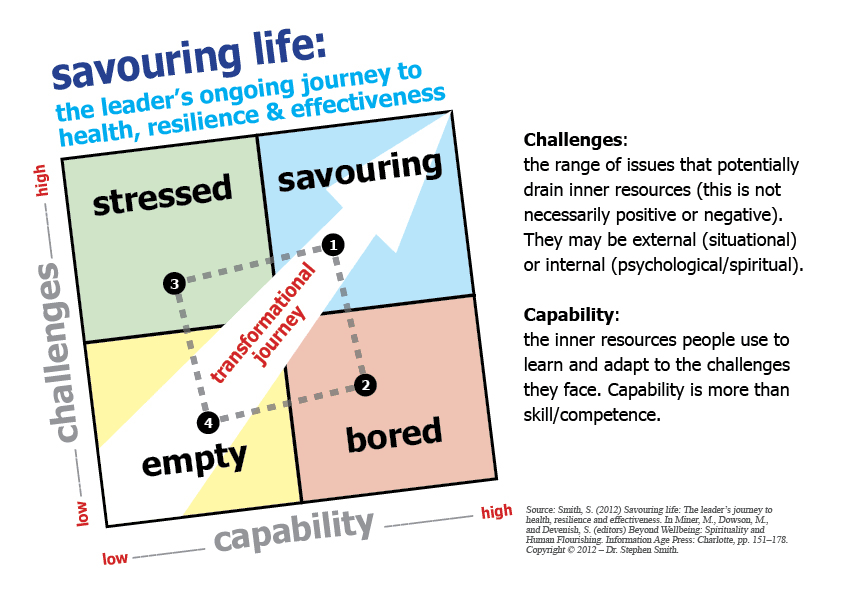

Stephen Smith’s (2012) research with 108 people helpers helped devise the following model: Savouring life—the leader’s journey to health, resilience and effectiveness (see the figure below). So many research participants had experienced stress, boredom or emptiness as a result of working harder and harder, like on a treadmill, hoping that somehow things would get better than they were today.

In contrast, the concept of the optimum functioning of a leader was referred to as “savouring life.” This was about being fully present in the moment, single-minded, focused and highly engaged – not so much about doing as about being. This is where the whole person—head (cognitive, thinking) heart (emotional, feeling) and hands (physical, doing)—is fully absorbed in what they are doing. This state of savouring has a positive effect on physical health, psychological well-being, workplace safety, personal resilience, cognitive functioning and life satisfaction. The capacity for savouring life supports the many attitudes and actions that contribute to overall human flourishing.

Figure: Savouring Life

The two dimensions of this model (see figure above) are challenges and capability:

Challenges are the range of issues that potentially drain inner resources (this is not necessarily positive or negative). They may be external (situational) or internal (psychological/spiritual).

Capability is essentially the inner resources people use to learn and adapt to the challenges they face. Capability is more than skill/competence.

The need to continuously adapt, savouring life, rather than merely enduring work, is exhibited in the following story.

John’s journey

John takes a job as the manager of a division in a welfare organisation. He is excited about the new adventure—it will be a fresh experience, stretching his capabilities as he faces new and unknown challenges. He has the ability to try creative ideas, apply things he has learned from different contexts and build relationships with a large team who are looking to him to be a significant leader who can help them move ahead. Expectations are high. John is absorbed in this new role—it is fun and energising. He knows he is making a real difference in the lives of the people he leads and the clients he encounters. He is focused, fully engaged, healthy, resilient and effective. This is the Savouring Quadrant (1).

Being in the Savouring Quadrant (1) is not merely being happy in what you are doing. Aristotle argued that there were two forms of happiness: hedonia (the life of pleasure) and eudaimonia (the life of purpose). Hedonic well-being is about maximising pleasure through indulging in the pursuit of appetites and desires. Eudaimonic well-being is optimum functioning based on the pursuit of goals and meaning. Aristotle viewed this as the higher pursuit. Each needs the other for holistic wellness. Pleasure without purpose is empty and meaningless. Purpose without pleasure is sterile and joyless. Seligman (2002) explores this duality:

The good life consists in deriving happiness by using your signature strengths in every day in the main realms of living. The meaningful life adds one more component: using these same strengths to forward knowledge, power or goodness. A life that does this is pregnant with meaning, and if God comes at the end, such a life is sacred. (p. 260)

Being in this quadrant is a meaningful experience for John. It is reflected in his overall wellness and effectiveness. Over time, John hits some limitations in his ability to keep going. For some reason, the role is no longer energising him and projects do not have the same excitement. They are now just regular events and start to have a feel of sameness (to him and others). To remain in the Savouring Quadrant there must be discovery and growth, being stretched to find inner strength and resources that were previously untapped. If the leader does not continue to learn, adapt proactively, and remain connected to the deeper values that brought him to the role, she or he will start to slide into the Stressed Quadrant (not having enough leadership abilities to deal with the significant challenges he faces) or the Bored Quadrant (having high capability but low challenges to face). At this point, the ‘honeymoon’ is over.

In the Bored Quadrant (2), the leader simply does not have enough challenges to keep the role interesting. One pastoral minister in this situation commented, ‘I can do what they expect of me in about two days a week’. The leader may create other ancillary roles to alleviate this state, focusing on those things that provide them with some form of energy—perhaps writing, social activities, creative expression, research study or service projects. Many para-church organisations have been effectively established by ministry leaders who were bored in their local ministry setting and redirected their energies into a new challenge. However, remaining in this state for an extended period will likely shift the leader into the Empty Quadrant.

In the Stressed Quadrant (3), leaders do not have the capability to meet the challenges they face. They may never have been up to the challenge, or may have been effective in leading the church to its current state but now feels somewhat lost, not knowing what to do next. Situational context is important—there may be a range of issues that now limit the capability or capacity of the leader (such as lack of work resources, shift in health status, change in family situation and lack of personal finances). As this realisation mounts in the leaders and in those around them, the stress is significant and, if unchecked, will push the leaders into the Empty Quadrant.

In the Empty Quadrant (4), the leader has mentally and emotionally ‘checked out’. Unresolved, chronic boredom and/or stress have a natural entropy towards living on ‘automatic pilot’. Often depressed and burned out, they are now barely hanging in there. Preoccupied with coping, they are unfocused, apathetic and disconnected from those around them. Their resilience is low and they are no longer professionally effective at all. To ease the pain, they may ‘adventure seek’ in ways that would normally be out of character, seeking small reprieves to an inner woundedness. These activities may be self-destructive as they move to a point beyond caring. Derailing activities may involve addiction or pleasure seeking. With a lowered ability to experience pleasure, they are robbed of joy and feel an emptiness within. While it is obvious to many it is time to stop, have a break and move on to something else, issues of financial security become significant and ministers sometimes hang on beyond the point of healthy closure. An inability to think clearly, process emotionally and limited options can result in feelings of being trapped.

Every leader moves through these quadrants, sometimes quickly, sometimes slowly and not necessarily in a particular sequence. One research participant said, ‘I can go through all of these in a day!’ However, it is the chronic states of these areas that can prove troublesome with stressed or bored sliding, over time, into emptiness.

https://colloquiumgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/1181712.jpg

1000

1500

Stephen Smith

https://colloquiumgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/the-colloquium-group-logo1-1.svg

Stephen Smith2022-11-17 12:49:212024-02-03 14:09:16Tool: Fostering a trusting team

https://colloquiumgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/1181712.jpg

1000

1500

Stephen Smith

https://colloquiumgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/the-colloquium-group-logo1-1.svg

Stephen Smith2022-11-17 12:49:212024-02-03 14:09:16Tool: Fostering a trusting team https://colloquiumgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/1181712.jpg

1000

1500

Stephen Smith

https://colloquiumgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/the-colloquium-group-logo1-1.svg

Stephen Smith2022-11-17 12:49:212024-02-03 14:09:16Tool: Fostering a trusting team

https://colloquiumgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/1181712.jpg

1000

1500

Stephen Smith

https://colloquiumgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/the-colloquium-group-logo1-1.svg

Stephen Smith2022-11-17 12:49:212024-02-03 14:09:16Tool: Fostering a trusting team